James Hunt

James Hunt | |

|---|---|

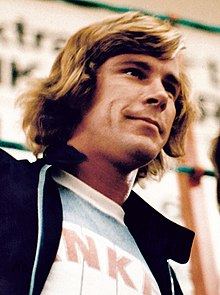

Hunt at the 1977 Swedish Grand Prix | |

| Born | James Simon Wallis Hunt 29 August 1947 Belmont, Surrey, England |

| Died | 15 June 1993 (aged 45) Wimbledon, London, England |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | David Hunt (brother) |

| Formula One World Championship career | |

| Nationality | |

| Active years | 1973–1979 |

| Teams | Hesketh, McLaren, Wolf |

| Entries | 93 (92 starts) |

| Championships | 1 (1976) |

| Wins | 10 |

| Podiums | 23 |

| Career points | 179 |

| Pole positions | 14 |

| Fastest laps | 8 |

| First entry | 1973 Monaco Grand Prix |

| First win | 1975 Dutch Grand Prix |

| Last win | 1977 Japanese Grand Prix |

| Last entry | 1979 Monaco Grand Prix |

James Simon Wallis Hunt (29 August 1947 – 15 June 1993) was a British racing driver and broadcaster, who competed in Formula One from 1973 to 1979. Nicknamed "The Shunt",[a] Hunt won the Formula One World Drivers' Championship in 1976 with McLaren, and won 10 Grands Prix across seven seasons.

Born and raised in Surrey, Hunt began his racing career in touring cars before progressing to Formula Three in 1969, where he attracted the attention of Lord Hesketh, founder of Hesketh Racing. Hunt earned notoriety throughout his early career for his reckless and action-packed exploits on track, amongst his playboy lifestyle off it. He signed for Hesketh in 1973—driving a March 731 chassis designed by Harvey Postlethwaite—making his Formula One debut at the Monaco Grand Prix. Hunt found immediate success in the sport, taking podiums in his rookie season at the Dutch and United States Grands Prix. Hesketh entered their own 308 chassis in 1974, in which Hunt scored several podiums and won the non-championship BRDC International Trophy. Retaining his seat the following season, Hunt scored his maiden win with Hesketh at the Dutch Grand Prix, widely regarded as one of the greatest underdog victories in Formula One history. Despite this, the team was left without sponsorship at the end of the season, leading Hunt to join McLaren for his 1976 campaign. Amidst a fierce title battle with Niki Lauda, Hunt won the World Drivers' Championship by a single point in his first season with McLaren. Despite winning several races in 1977, he fell to fifth in the standings due to poor reliability. After a winless season for McLaren in 1978, Hunt moved to Wolf and retired after the 1979 Monaco Grand Prix, having achieved 10 race wins, 14 pole positions, eight fastest laps and 23 podiums in Formula One.

Upon retiring from motor racing, Hunt established a career as a commentator and pundit for the BBC. Through Marlboro, he also mentored two-time Formula One World Champion Mika Häkkinen. He died from a heart attack at his home in Wimbledon, aged 45.

Early life

[edit]Hunt was born in Belmont, Surrey, the second child of Wallis Glynn Gunthorpe Hunt (1922–2001), a stockbroker, and Susan (Sue) Noel Wentworth (née Davis) Hunt.[1][2] He had an elder sister, Sally, three younger brothers, Peter, Timothy and David, and one younger sister, Georgina.[3] Wallis Hunt was descended on his mother's side from the industrialist and politician Sir William Jackson, 1st Baronet.[4] Hunt's family lived in a flat in Cheam, Surrey, moved to Sutton when he was 11 and then to a larger home in Belmont.[5] He attended Westerleigh Preparatory School, St Leonards-on-Sea Sussex[6] and later Wellington College.[7]

Hunt first learned to drive on a tractor on a farm in Pembrokeshire, Wales, while on a family holiday, with instruction from the farm's owner, but he found changing gears frustrating because he lacked the required strength.[8] Hunt passed his driving test one week after his seventeenth birthday, at which point he said his life "really began".[9] He also took up skiing in 1965 in Scotland, and made plans for further ski trips. Before his eighteenth birthday, he went to the home of Chris Ridge, his tennis doubles partner. Ridge's brother Simon, who raced Minis, was preparing his car for a race at Silverstone that weekend. The Ridges took Hunt to see the race, which began his obsession with motor racing.[10]

Early career

[edit]Mini racing

[edit]Hunt's racing career started off in a racing Mini. He first entered a race at the Snetterton Circuit in Norfolk, but race scrutineers prevented him from competing, deeming the Mini to have many irregularities, which left Hunt and his team mate, Justin Fry, upset. Hunt later brought the necessary funding from working as a trainee manager of a telephone company to enter three events. At this point Fry made the decision to part company with the team, owing to the irregularities and modifications that were happening to the cars they were using.[11]

Formula Ford

[edit]Hunt graduated to Formula Ford in 1968. He drove a Russell-Alexis Mark 14 car bought through a hire-purchase scheme. In his first race at Snetterton, Hunt had lost 15 hp from an incorrect engine ignition setting, but managed to finish fifth. Hunt took his first win at Lydden Hill and also set the lap record on the Brands Hatch short circuit.[12]

Formula Three

[edit]

In 1969, Hunt raced in Formula Three with a budget, provided by Gowrings of Reading, which bought a Merlyn Mark 11A. Gowrings intended to run the car in the final two races of 1968.[12] Hunt won several races and achieved regular high-placed finishes, which led to the British Guild of Motoring Writers awarding him a Grovewood Award as one of the three drivers judged to have promising careers.[13]

Hunt was involved in a controversial incident with Dave Morgan during a battle for second position in the Formula Three Daily Express Trophy race at Crystal Palace on 3 October 1970. Having banged wheels earlier in a very closely fought race, Morgan attempted to pass Hunt on the outside of South Tower Corner on the final lap, but instead the cars collided and crashed out of the race. Hunt's car came to rest in the middle of the track, minus two wheels. Hunt got out, ran over to Morgan and furiously pushed him to the ground,[14] which earned him severe official disapproval. Both men were summoned by the RAC and after hearing evidence from other drivers, Hunt was cleared by a tribunal and Morgan was given a 12-month suspension of his racing licence, but was subsequently allowed to progress to Formula Atlantic in 1971.[15] Hunt later met with John Hogan and racing driver Gerry Birrell to obtain sponsorship from Coca-Cola.[16]

Hunt's career continued in the works March team for 1972. His first race at Mallory Park saw him finish third, but he was told by race officials he had been excluded from the results, as his engine was deemed to be outside the regulations.[17] The car, however, passed tests at the next two races at Brands Hatch. In these races, Hunt finished fourth and fifth respectively. He collided with two cars at Oulton Park but finished third at Mallory Park after a long duel with Roger Williamson. The cars did not appear at Zandvoort, but Hunt still attended the race as a spectator.[18]

In May 1972, it was announced by the team that he had been dropped from the STP-March Formula 3 team and replaced by Jochen Mass. When Hunt attempted to contact March, he was unable to get any response from his employers. Hunt decided to consult Chris Marshall, his former team manager, who explained that a spare car was available.[18] This followed a period characterised by a series of mechanical failures. Hunt decided, against the express instructions of March director Max Mosley, to race at Monaco in a March from a different team. This had been vacated by driver Jean-Claude Alzerat, after Hunt's own March had first broken down and then been hit by another competitor in a practice lap.[19]

Formula One career

[edit]1973–1975: Hesketh

[edit]- 1973

Hesketh purchased a March 731 chassis, and it was developed by Harvey Postlethwaite. The team was initially not taken seriously by rivals, who saw the Hesketh team as party goers enjoying the glamour of Formula One.[Note 1] However, the Hesketh March proved much more competitive than the works March cars, and their best result was second place at the 1973 United States Grand Prix. Hunt also made a brief venture into sports car racing at the 1973 Kyalami Nine Hours, driving a Mirage M6 along with Derek Bell, finishing second.[22]

After the season's end, Hunt was awarded with the Campbell Trophy from the RAC marking his performance in Formula One as the best by a British driver.[23]

- 1974

For the 1974 season, Hesketh Racing built a car, inspired by the March, called the Hesketh 308, but an accompanying V12 engine never materialised. Hunt's first test of the car came at Silverstone and found it more stable than its predecessor, the March 731. Hunt was retained on a £15,000 salary.[24] The Hesketh team captured the public imagination as a car without sponsors' markings, a teddy-bear badge and a devil-may-care team ethos, which belied the fact that their engineers were highly competent professionals. In Argentina, Hunt qualified fifth and led briefly before being overtaken by Ronnie Peterson before Hunt spun off the track and eventually retired due to engine failure.[25] In South Africa, Hunt retired from fifth place with a broken driveshaft.[26] Hunt's season highlight was a victory at the BRDC International Trophy non-championship race at Silverstone, against the majority of the regular F1 field.

- 1975

Hunt finished sixth in Brazil and retired with an engine failure in South Africa. In Spain, Hunt led the first six laps before colliding with a barrier with the same cause of retirement in Monaco. He had a further two retirements in Belgium and Sweden, both of which were due to mechanical failures.[27] Hunt's first win came in the 1975 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. He finished fourth in the Championship that year, but Lord Hesketh had run out of funds and could not find a sponsor for his team. With little time left before the 1976 season, Hunt was desperately looking for a drive until Emerson Fittipaldi left McLaren and joined his brother's Copersucar-Fittipaldi outfit. With no other top drivers available, the team management signed Hunt to McLaren – in a deal brokered by Marlboro's John Hogan – for the next season on a contract involving a $50,000 retainer and a good share of the prize money.[28]

1976–1978: McLaren

[edit]

- 1976

The season proved to be one of the most dramatic and controversial on record. While Hunt's performances in the Hesketh had drawn considerable praise, there was some speculation as to whether he could really sustain a championship challenge. Now a works McLaren driver, he dispelled many doubters at the first race in Brazil, where, in a hastily rebuilt McLaren M23, he landed pole position in the last minutes of qualifying. Over the course of the year he would drive the McLaren M23 to six Grands Prix wins, but with superior reliability reigning world champion and main rival Niki Lauda had pulled out a substantial points lead in the first few races of the season. Hunt's first race win of 1976, at the fourth race of the season, the Spanish Grand Prix, resulted in disqualification for driving a car adjudged to be 1.8 cm too wide. The win was later reinstated upon appeal, but it set the tone for an extraordinarily volatile season. At the British Grand Prix, Hunt was involved in a first corner incident on the first lap with Lauda which led to the race being stopped and restarted. Hunt initially attempted to take a spare car, however this was disallowed, and during this time the original race car was repaired, eventually winning the restarted race.[29] Hunt's victory was disallowed on 24 September by a ruling from the FIA after Ferrari complained that Hunt was not legally allowed to restart the race.[30]

Lauda sustained near-fatal injuries in an accident at the following round, the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring. Hunt dominated the restarted Nürburgring race, building an immediate lead and remaining unchallenged to the chequered flag.

Lauda's injuries kept him out of the following two races, allowing Hunt to close the gap in the championship chase. At Zandvoort, Hunt overtook Ronnie Peterson on the 12th lap and resisted pressure from John Watson to win.[31] At the Italian Grand Prix, the big story was Lauda's miraculous return from his Nürburgring accident. At a circuit that should have suited Hunt's car, the Texaco fuel McLaren were using was tested and although apparently legal, their cars, and those of the Penske team, were judged to contain a higher octane level than allowed. Subsequently, both teams were forced to start from the rear of the grid. While trying to make his way up the field, Hunt spun off, and Lauda finished fourth. At the next round in Canada, Hunt found out that he had been disqualified from the British Grand Prix and Lauda had been awarded the victory and thus received three additional points. A furious Hunt drove a very hard race at the challenging Mosport Park circuit and won. At the penultimate round in the United States at the daunting Watkins Glen track, Hunt started from pole and took victory after a close battle with Jody Scheckter.[32] This set the stage for the final round in Japan. Hunt's late season charge pulled him to just three points behind Lauda. The sliding scale of points for the top six finishers meant that Hunt needed to finish fourth (worth 3 points) or better to overtake Lauda in the championship. Lauda needed to earn two points fewer than Hunt, or better, to stay ahead. McLaren team manager Alastair Caldwell had taken advantage of the gap between the final two races to hire the Fuji circuit – a track hosting its first Grand Prix and therefore unknown to all the teams – for an exclusive McLaren test. After a few laps the gearbox seized, bringing the test to a premature close, but the team had had the advantage of acclimatising themselves to the new circuit. Conditions for the race itself were torrentially wet. Lauda retired early on in the race, unable to blink because of facial burns from his accident in Germany.[33] After leading most of the race Hunt suffered a puncture, then had a delayed pitstop and finally received mixed pit signals from his team. But he managed to finish in third place, scoring four points, enough for him to win the World Championship by one point.[34] Hunt was the last British Formula One champion until Nigel Mansell won the 1992 championship for Williams.[35] He was, relatively, one of the cheapest F1 World Champions ever, having signed at the last minute for $200,000 – a scenario similar to that of 1982 champion Keke Rosberg.[citation needed]

- 1977

Before the start of 1977, Hunt attended a gala function at the Europa Hotel in London where he was awarded the Tarmac Trophy, along with two cheques, for £2000 and £500 respectively, a magnum of champagne and other awards. The presentation was made by the Duke of Kent. Hunt made an acceptance speech after the event which was considered "suitably gracious and glamorous". The media were critical of Hunt as he attended the event dressed in jeans, T-shirt and a decrepit windbreaker.[36]

Before the South African Grand Prix, Hunt was confronted by customs officials who searched his luggage, finding no illegal substances except a publication that contravened the strict obscenity laws of South Africa. Hunt was later released, and tested at Kyalami where his McLaren M26 suffered a loose brake caliper which cut a hole in one of the tyres. He recovered and put the car on pole position. The race saw Hunt suffer a collision with Jody Scheckter's Wolf and another with Patrick Depailler's Tyrrell, but he still managed to finish fourth.[37]

The season did not start well for Hunt. The McLaren M26 was problematic in the early part of the season, during which Niki Lauda, Mario Andretti and Jody Scheckter took a considerable lead in the Drivers' Championship. Towards the end of the year Hunt and the McLaren M26 were quicker than any rival combination other than Mario Andretti and the Lotus 78. Hunt won in Silverstone after trailing the Brabham of John Watson for 25 laps.[38] He then took a further victory at Watkins Glen. At the Canadian Grand Prix, Hunt retired after a collision with team-mate Jochen Mass and was fined $2000 for assaulting a marshal and $750 for walking back to the pit lane in an "unsafe manner".[39] In Fuji, Hunt won the race but did not attend the podium ceremony[40] resulting in a fine of $20,000.[41] He finished fifth in the World Drivers' Championship.

- 1978

Before the 1978 season Hunt had high hopes to win a second world championship; however, in this season he scored only eight world championship points. Lotus had developed effective ground effect aerodynamics with their Lotus 79 car and McLaren were slow to respond. The M26 was revised as a ground effect car midway through the season but it did not work, and without a test driver to solve the car's problems, Hunt's motivation was low. His inexperienced new team-mate Patrick Tambay even outqualified Hunt at one race. In Germany, Hunt was disqualified for taking a shortcut to allow for a tyre change.[42]

Hunt was also greatly affected by Ronnie Peterson's fatal crash in the 1978 Italian Grand Prix. At the start of the race there was a huge accident going into the first corner. Peterson's Lotus was pushed into the barriers and burst into flames. Hunt, together with Patrick Depailler and Clay Regazzoni, rescued Peterson from the car, but Peterson died one day later in hospital. Hunt took his friend's death particularly hard and for years afterwards blamed Riccardo Patrese for the accident.[43] He never forgave Patrese for the crash. Video evidence of the crash has since shown that Patrese did not touch Hunt or Peterson's cars, nor did he cause any other car to do so.[44] Hunt believed that it was Patrese's muscling past that caused the McLaren and Lotus to touch, but Patrese argues that he was already well ahead of the pair before the accident took place.[44]

1979: Walter Wolf Racing

[edit]

For 1979, Hunt had resolved to leave the McLaren team. Despite his poor season in 1978 he was still very much in demand. Harvey Postlethwaite persuaded Hunt to join Walter Wolf Racing – a one-car team where he would have found an atmosphere similar to the one he had experienced at Hesketh at the beginning of his career. Again he had high hopes to win races and compete for the world championship in what would be his last, and ultimately brief, Formula One season. The team's ground effect car was uncompetitive and Hunt soon lost any enthusiasm for racing.[45] Hunt could only watch as Jody Scheckter won the World Drivers' Championship that year driving the Ferrari 312T4.

At the first race in Argentina, he felt the car was difficult to handle and on a fast lap, the front wing became detached striking his helmet. In the race, Hunt retired due to an electrical fault. In Brazil, he retired on lap 6 due to instability under braking caused by a loose steering rack. During qualifying in South Africa, the brakes on his car failed. He managed not to collide with the wall, but only finished 8th in the race. He retired at the Spanish Grand Prix after 26 laps. At Zolder, a new Wolf WR8 was raced but Hunt crashed into a barrier hard enough to bounce back onto the track. After failing to finish the 1979 Monaco Grand Prix, the race where six years previously he had made his debut, Hunt made a statement on 8 June 1979 to the press announcing his immediate retirement from F1 competition, citing his situation in the championship, and was replaced by future world champion Keke Rosberg.[46] Despite going into retirement, he continued to work to promote his personal sponsors Marlboro and Olympus.[47] According to Peter Warr, Hunt had been badly affected by the Ronnie Peterson accident in Monza the year before and his heart was no longer in it. Warr recalled Hunt telling him that he discovered that if he nudged the car up against the barrier and give it a squirt of throttle in second gear, it would break a driveshaft. "At Monaco, four laps into the race, James stopped up the hill by Rosie's bar, with a broken driveshaft. Then he told us he was retiring."[48]

Later career (1979–1993)

[edit]Commentary career

[edit]Soon after retirement, in 1979, Hunt was approached by Jonathan Martin, the head of BBC television sport, to become a television commentator alongside Murray Walker on the BBC 2 Formula One racing programme Grand Prix. After a guest commentary at the 1979 British Grand Prix, Hunt accepted the position and continued for thirteen years until his death. During his first live broadcast at the 1980 Monaco Grand Prix, Hunt placed his plaster-cast leg into Walker's lap and drank two bottles of wine during the broadcast.[49][50] Hunt regularly went into the booth minutes before a race started, which concerned Martin, who believed that Hunt was "a guy that lived on adrenaline."[51]

In the commentary booth, the producers supplied only one microphone to Walker and Hunt, to avoid them talking over each other. On one occasion, Hunt wanted the microphone and went up to Walker, who had continued for longer than expected, and grabbed him by the collar, with Walker having his fist near to Hunt.[52] On another occasion, Hunt grabbed the microphone cord and cracked it like a whip, which yanked the microphone out of Walker's hand. His insights and dry sense of humour brought him a new fanbase. He often heavily criticised drivers he did not think were trying hard enough – during the BBC's live broadcast of the 1989 Monaco Grand Prix he described René Arnoux's comments that non-turbo cars did not suit the Frenchman's driving skills as "bullshit".[53] He also had a reputation for speaking out against back-markers who held up race leaders.[54]

Other than Arnoux, Hunt's other frequent targets included Andrea de Cesaris, Philippe Alliot, Jean-Pierre Jarier and Riccardo Patrese. Hunt criticised Jean-Pierre Jarier for blocking leaders, calling him "pig ignorant", a "French wally" and having a "mental age of ten" during live broadcasts.[citation needed][55] Hunt further suggested that Jarier should be banned from racing "for being himself".[56][57][58]

Hunt did not want his commentaries broadcast in South Africa during the apartheid years but when he could not stop this from happening, he gave his fees to black-led groups working to overthrow apartheid.[59]

Hunt also commented on Grand Prix racing in newspaper columns which were published in The Independent and elsewhere, and in magazines.[60]

Attempted comebacks

[edit]In 1980, Hunt nearly made a comeback with McLaren at the United States Grand Prix West, asking for $1 million for the race. This opportunity came about when regular driver Alain Prost broke his wrist during practice for the previous round in South Africa, and the French rookie was not fully fit to drive at Long Beach. The team's main sponsor, Marlboro, offered half the figure but negotiations ended after Hunt broke his leg while skiing. In 1982 Bernie Ecclestone, owner of the Brabham team, offered Hunt a salary of £2.6 million for the season but was rejected by Hunt. In 1990, Hunt was in financial trouble with the loss of £180,000 investing in Lloyd's of London[61] and considered a comeback with the Williams team. He had tested on the Paul Ricard Circuit a few months prior to test modern cars and was several seconds off the pace and believed he would be physically prepared. Hunt attempted to persuade John Hogan, VP Marketing of Philip Morris Europe,[62] to support the possible comeback, and presented him with bank statement for proof of being indebted.[63]

Other projects

[edit]Hunt made a brief appearance in the 1979 British silent slapstick comedy The Plank, as well as co-starring with Fred Emney in a Texaco Havoline TV advertisement. He also made a posthumous appearance on ITV's Police Camera Action! special Crash Test Racers in 2000; this was one of many interviews to be aired posthumously. Hunt also competed in an exhibition race to mark the opening of the new Nürburgring in May 1984.[64] Despite having no licence to ride a motorcycle, he accepted, instead of his usual fee, the then-new 1980 electric start Triumph Bonneville he had contracted to advertise on behalf of the struggling Triumph motorcycle workers' co-operative. With journalistic mirth, he turned up at the press launch with his foot in plaster.[65]

Hunt was hired by John Hogan as an adviser and tutor to drivers who were sponsored by Marlboro, instructing them in the tactics of driving and the approach to racing. Mika Häkkinen and Hunt had discussions about not only racing but about life in general.[51]

Personal life

[edit]Early in their careers, Hunt and Niki Lauda were friends off the track. Lauda occasionally stayed at Hunt's flat when he had nowhere to sleep for the night. In his autobiography To Hell and Back, Lauda described Hunt as an "open, honest to God pal." Lauda admired Hunt's burst of speed, while Hunt admired Lauda's capacity for analysis and rigour.[66] In the spring of 1974, Hunt moved to Spain on the advice of the International Management Group.[67] Whilst living there as a tax exile, Hunt was the neighbour of Jody Scheckter, and they also came to be very good friends, with Hunt giving Scheckter the nickname Fletcher after the crash-prone bird in the book Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Another close friend was Ronnie Peterson who was a quiet and shy man, whilst Hunt was the opposite, but their contrasting personalities made them very close off the track. It was Hunt who discovered Gilles Villeneuve, whom he met after being soundly beaten by him in a Formula Atlantic race in 1976. Hunt then arranged for the young Canadian to make his Grand Prix debut with McLaren in 1977.

Hunt claimed to have slept with 5000 women.[21] He was involved in a relationship with Taormina Rieck (known as Ping by her friends) from the age of 15.[9] Rieck separated from Hunt in May 1971, which left Hunt not seeing his family or friends for long periods of time.[68] Hunt met his first wife, Suzy Miller, in 1974 in Spain. A few weeks after their initial meeting, he proposed. The couple married on 18 October 1974 at the Brompton Oratory in Knightsbridge. By the end of 1975, Suzy had left Hunt for the actor Richard Burton.

In 1982, Hunt moved to Wimbledon.[69] In September that year, he met his second wife, Sarah Lomax, while she was on a holiday in Spain with friends. Hunt started dating Lomax when she arrived back in Britain, and they dated throughout the winter. Hunt and Lomax were married on 17 December 1983 in Marlborough, Wiltshire. Hunt arrived late for the service, with proceedings delayed further when his brother Peter went to a shop to purchase a tie for him.[70] The marriage resulted in two children, Tom and Freddie, the latter of whom is also a racing driver.[71][72]

On a visit to Doncaster, Hunt was arrested for an assault, which was witnessed by two police officers, and was released on bail after two hours with the charges against him later being dropped.[73] Hunt and Lomax separated in October 1988 but continued to live together for the best interests of their children. They were divorced in November 1989 on the grounds of adultery committed by Hunt.[74]

Hunt met Helen Dyson in the winter of 1989 in a restaurant in Wimbledon, where she worked as a waitress. Dyson was 18 years Hunt's junior and worried about her parents' reactions to him. Hunt kept the relationship secret from friends. The relationship brought new happiness to Hunt's life, among other factors which included his clean health, his bicycle, his casual approach to dress, his two sons and his Austin A35 van.[60] The day before he died, Hunt proposed to Dyson via telephone.[75]

Death

[edit]Hunt died in his sleep on the morning of 15 June 1993 of a heart attack at his home in Wimbledon.[76][77] He was 45 years old.

At his funeral service, the pallbearers included his father Wallis, his brothers Tim, Peter and David, and his friend Anthony 'Bubbles' Horsley. They carried the coffin out of the church and into the hearse, which drove two miles to Putney Vale Crematorium, where he was cremated. After the service, most of the mourners went to Peter Hunt's home to open a 1922 claret, the year of Wallis Hunt's birth. The claret had been given to him by James on his 60th birthday in 1982.[78]

Legacy

[edit]

Hunt was known as a fast driver with an aggressive, tail-happy driving style, but one prone to spectacular accidents, hence his nickname of Hunt the Shunt. In reality, while Hunt was not necessarily any more accident-prone than his rivals in the lower formulae, the rhyme stuck and stayed with him. In the book James Hunt: The Biography, John Hogan said of Hunt: "James was the only driver I've ever seen who had the vaguest idea about what it actually takes to be a racing driver."[51] Niki Lauda stated that "We were big rivals, especially at the end of the [1976] season, but I respected him because you could drive next to him—2 centimetres, wheel-by-wheel, for 300 kilometres or more—and nothing would happen. He was a real top driver at the time."[79]

After winning the world championship in 1976, Hunt inspired many teenagers to take up motor racing,[80] and he was retained by Marlboro to give guidance and support to up and coming drivers in the lower formulae. In early 2007, Formula One driver and 2007 World Champion Kimi Räikkönen entered and won a snowmobile race in his native Finland under the name James Hunt. Räikkönen has openly admired the lifestyles of 1970s race car drivers such as Hunt.[81] Hunt's name was lent to the James Hunt Racing Centre in Milton Keynes when it opened in 1990.[82]

A Celebration of the Life of James Hunt was held on 29 September 1993 at St James's Church, Piccadilly. The service was attended by 600 people and on 29 January 2014 James Hunt was inducted into the Motor Sport Hall of Fame.

Helmet

[edit]Hunt's helmet featured his name in bold letters along with blue, yellow and red stripes on both sides and room for the sponsor Goodyear, all set on a black background.[83] Additionally, the blue, yellow and red bands resemble his Wellington College school colours.[84] During his comeback year to Formula One in 2012, 2007 World Champion Kimi Räikkönen sported a helmet with the James Hunt's name printed on it during the Monaco Grand Prix.[85] Räikkönen repeated the tribute at the 2013 Monaco Grand Prix.[86]

In popular culture

[edit]The 1976 F1 battle between Niki Lauda and James Hunt was dramatised in the 2013 film Rush, in which Hunt was played by Chris Hemsworth. In the film, Lauda said of Hunt's death, "When I heard he'd died aged 45 of a heart attack I wasn't surprised, I was just sad". He also said that Hunt was one of the very few people he liked, a smaller number he respected and the only one he had envied.[87]

Racing record

[edit]Career summary

[edit]Complete British Saloon Car Championship results

[edit](key) (Races in bold indicate pole position; races in italics indicate fastest lap.)

| Year | Team | Car | Class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | DC | Pts | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Nightingale | Hillman Imp | A | BRH | SNE | THR | SIL 29 |

CRY | SIL Ret |

SIL | CRO | BRH Ret |

OUL | BRH | BRH | NC | 0 | NC |

Complete Formula One World Championship results

[edit](key) (Races in bold indicate pole position, races in italics indicate fastest lap)

* Hunt was initially disqualified due to his car being deemed illegal, but later reinstated after McLaren successfully appealed the decision.

Formula One non-championship results

[edit](key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) (Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Hesketh Racing | Surtees TS9 | Ford V8 | ROC 3 |

INT | |

| 1974 | Hesketh Racing | March 731 | Ford V8 | PRE Ret |

||

| Hesketh 308 | Ford V8 | ROC Ret |

INT 1 | |||

| 1975 | Hesketh Racing | Hesketh 308 | Ford V8 | ROC | INT Ret |

SUI 7 |

| 1976 | Marlboro Team McLaren | McLaren M23 | Ford V8 | ROC 1 |

INT 1 |

|

| 1977 | Marlboro Team McLaren | McLaren M23 | Ford V8 | ROC 1 |

||

| 1978 | Marlboro Team McLaren | McLaren M26 | Ford V8 | INT Ret |

||

| 1979 | Wolf Racing | Wolf WR8 | Ford V8 | ROC | GNM 2 |

DIN |

Source:[88]

| ||||||

Notes

[edit]- ^ In British motorsport terminology, shunt means a collision.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

Citations

- ^ Thoms, David (23 September 2004). "Hunt, James Simon Wallis (1947–1993), racing driver and commentator". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52127. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Driver: Hunt, James". Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Autocourse Grand Prix Archive, 14 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007. - ^ Young and Hunt 1978, p. 9.

- ^ Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, ed. Arthur G. M. Hesilrige, Kelly's Directories, 1931, p. 426

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 11–12.

- ^ "360 pupils to find new places as private school closes". Hastings & St Leonards Observer. 29 April 2004. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ "McLaren Racing - The man, the myth, the legend". www.mclaren.com. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 16–19.

- ^ a b Donaldson 1994, pp. 24–30.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 41–43.

- ^ a b Donaldson 1994 pp. 43–45.

- ^ Donalson 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Goddard, Jeff (Producer), Walker, Murray (Commentator). "Daily Express Trophy Final, October 1970." 100 Great Sporting Moments (BBC-BBC Two, Airdate 1993.

- ^ Steve Small. The Guinness Complete Grand Prix Who's Who. p. 260. ISBN 0851127029.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 61–62.

- ^ "1972 Formula 3 Season". primotipo.com. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ a b Donaldson 1994, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Skilleter, Paul (Charles Bulmer, ed.). "Sporting side: Hunt out – Mass in." Motor, 3 June 1972, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 142.

- ^ a b Wills, Kate (4 October 2024). "The privately educated law student at the heart of the F1 love triangle". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ McDonough 2012, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 114.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 118.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 122.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Dodgins, Tony; Webber, Mark. Formula One: The Rivals: F1's Greatest Duels. p. 82.

- ^ "Hunt wins third grand prix in the confusion." The Glasgow Herald, 19 July 1976, p. 14.

- ^ "James Hunt set for war". The News-Dispatch, 9 October 1976, p. 8.

- ^ "Dutch Grand Prix Hunt's Birthday Gift."The Pittsburgh Press, 30 August 1976, p. 18.

- ^ "Hunt Captures US Grand Prix; Ickx Injured."[permanent dead link] The Milwaukee Sentinel, 11 October 1976, p. 9B.

- ^ Rubython 2010, p. 243.

- ^ "Lauda withdrawal [sic] gives Hunt title". Ottawa Citizen, 26 October 1976, p. 19.

- ^ "James Hunt's death shocks racing world". The Vindicator, 16 June 1993, p. C3.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 254.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 257–259.

- ^ "James Hunt Wins Grand Prix Event."Sarasota Herald-Tribune, 18 July 1977, p. 2C.

- ^ Williamson, Martin. "'Hunt the punch'." ESPN, 11 June 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Medland, Chris. "Fuji's failed finale".ESPN, 4 October 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ "Hunt snubs Grand Prix ceremony." The Age, 25 October 1977, p. 38.

- ^ "Andretti Wins Prix; Nears Formula Title".[permanent dead link] The Milwaukee Journal, 31 July 1978, p. 4 (Part 2).

- ^ "8W – Who? -James Hunt." 8w.forix.com. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ a b Widdows, R. "Patrese: more sinned against than sinning?" Motor Sport, 83/11, November 2007, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Rubython 2010, p. 270.

- ^ "James Hunt to retire." The Rock Hill Herald, 8 June 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 300–305.

- ^ "Lunch with... Peter Warr". 7 July 2014.

- ^ "James 'Hunt The Shunt', The 1970's High-Flyin' Lothario of Formula 1." The Selvedge Yard, 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Trackside: Remembering James Hunt." Auto Trader, 30 November 2006.

- ^ a b c Donaldson 1994, pp. 312–313.

- ^ "Murray Walker: Life in the Fast Lane" (Television Production and video). BBC (London), Airdate 2011.

- ^ Walker, Murray and James Hunt, (Commentators) (7 May 1989). "Monaco Grand Prix May, 7 1989". 1. Season 1989. BBC. BBC Two.

- ^ Walker, Murray, and James Hunt, (Commentators). "Portuguese Grand Prix September 23, 1990". 1. Season 1990. BBC.

- ^ James Hunt Savage Commentary, 27 August 2020, retrieved 27 September 2023

- ^ Walker, Murray and James Hunt, (Commentators) (14 August 1983). "Austrian Grand Prix August, 14 1983". 1. Season 1983. BBC. BBC Two.

- ^ "Happy birthday, Jean-Pierre Jarier!". richardsf1.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ James Hunt: "Jarier has a mental age of 10" on YouTube

- ^ "Guardian diary Thursday 15th August 2013". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ a b Tremayne, David."Obituary: James Hunt." The Independent, 16 June 1993. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "James Hunt 'faced 180,000 pounds losses at Lloyd's'." The Independent, 21 June 1993.

- ^ "John Hogan."Grand Prix.com. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Edmondson, Laurence."Twenty equal cars, one winner." ESPN, 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Rosamond 2009, p. 183.

- ^ Chimits et al. 2008, pp. 90–93.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 128.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Stock, Jon."For sale: F1 star James Hunt's London home". The Telegraph, 16 October 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 321

- ^ "James Hunt: Biography."IMDb. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Freddie Hunt." Archived 11 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine freddiehunt.com. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 332.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, pp. 346–354.

- ^ "James Hunt". The Official Formula 1 Website. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ Siano, Joseph (16 June 1993). "James Hunt, 45, Race-Car Driver Known for Style as Well as Title". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 357.

- ^ Stern, Marlow (27 September 2013). "Almost fatal: Legendary Formula One racer Niki Lauda on the season that nearly killed him". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Formula 1's Greatest Drivers: No. 24, James Hunt". Autosport. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ Benson, Andrew."Raikkonen the playboy king". BBC Sport, 21 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 337.

- ^ "James Hunt helmet a 'nice design'." ESPN, 25 May 2012.

- ^ Donaldson 1994, p. 34.

- ^ "Formula One qualifying 2012 at Monaco". Formula One. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Raikkonen told to cover up James Hunt helmet tribute". ESPN. 25 May 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ Niki Lauda on James Hunt, Graham Bensinger, 11 October 2017.

- ^ "James Hunt – Involvement Non World Championship". StatsF1. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

Bibliography

- Chimits, Xavier, Bernard Cahier and Paul-Henri Cahier. Grand Prix Racers: Portraits of Speed.[permanent dead link] St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7603-3430-0.

- Donaldson, Gerald: James Hunt: The Biography. London: Virgin Books, 1994. ISBN 978-0-7535-1823-6.

- McDonough, Ed. Gulf-Mirage 1967 to 1982. Dorchester, UK: Veloce, 2012. ISBN 978-1-845842-51-2.

- Rosamond, John. Save The Triumph Bonneville: The Inside Story Of The Meriden Workers' Co-Op. Dorchester, UK: Veloce, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84584-265-9.

- Rubython, Tom. In the Name of Glory: 1976, The Greatest Ever Sporting Duel. London: The Myrtle Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-95656-569-3.

- Rubython, Tom. Rush to Glory: Formula 1 Racing's Greatest Rivalry. London: The Myrtle Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7627-9696-0.

- Rubython, Tom. Shunt: The Story of James Hunt. London: The Myrtle Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-956-565-600.

- Young, Eoin and James Hunt. James Hunt: Against All Odds. London: Dutton, 1978. ISBN 978-0-525-1362-55.

External links

[edit]- 1947 births

- 1993 deaths

- BBC sports presenters and reporters

- BRDC Gold Star winners

- British Formula Three Championship drivers

- Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery

- English Formula One drivers

- English racing drivers

- European Formula Two Championship drivers

- Formula One World Drivers' Champions

- Formula One race winners

- Grovewood Award winners

- Hesketh Formula One drivers

- International Race of Champions drivers

- McLaren Formula One drivers

- Motorsport announcers

- People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire

- People from Sutton, London

- Sportspeople from the London Borough of Sutton

- British sports broadcasters

- Wolf Formula One drivers

- Deaths from coronary artery disease